NEW: You can view online presentations about our work on this topic here and here.

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a devastating neurodegenerative disease that has as its primary genetic cause a mutation in the huntingtin (HTT) protein. Expansion of a CAG repeat in the HTT gene results in a “gain of toxicity” that leads to neuronal cell death via poorly understood mechanisms. Much or most of the toxicity is due to misfolded forms of the mutant HTT protein, which in its mutant form features an expanded polyglutamine (polyQ) segment. The misfolded protein self-assembles into differently structured protein assemblies that enhance cellular toxicity or act as a “safety mechanism” that removes other, toxic species of mutant HTT and its fragments. In either case, HTT protein aggregates are an important biomarker in HD.

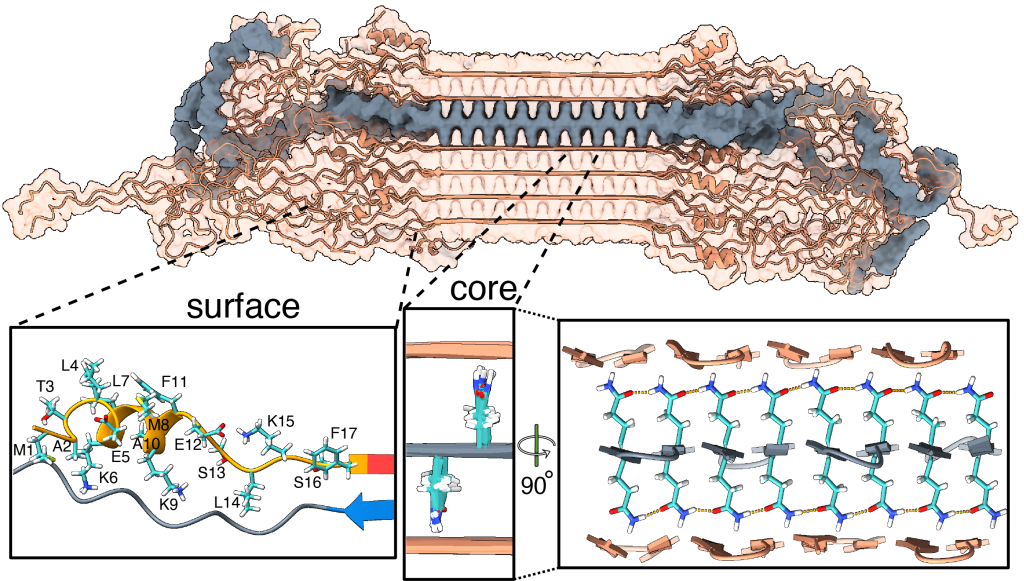

We have been using ssNMR spectroscopy to elucidate the conformation of the protein fibrils and understand how they form. Since 2010, we have shown that htt exon1 and other polyQ aggregates share a similarly structured polyQ amyloid core. These fibrils, made in vitro, are found to be toxic to human neuronal cells [7]. We showed that the polyQ core of aggregated mutant HTT exon1 contains a β-hairpin structure[6], whose formation is a pivotal step in the protein aggregation process [3]. The HTT domains flanking polyQ have dramatic effects on the misfolding and aggregation behavior, but are not incorporated into this amyloid core [1,4,5,7]. Instead, in the fibrils the N-terminal segment (httNT, or N17) features an α-helix that is solvent-exposed [1,5,7]. In Dec 2024 we reported a collaborative paper on an integrative structural biology model of the HTTex1 fibrils (in their mutant form) [8]. An image from the paper is included below in Figure 2, and more information is in this news posting. We are continuing our studies of the misfolded protein aggregates to determine how chaperones, antibodies and other htt-binding proteins can be used to modulate the disease-causing misfolding and aggregation process.

Funding

Our work on HD research has been funded by various sources, including the American NIH (via NIGMS and NIA), the Dutch Campagneteam Huntington, CHDI Foundation, and the EHDN. We are very grateful for their past and current support and do our best to turn this support into new insights into HD mechanisms, diagnostic tools and potential treatment strategies.

Related publications from the lab

- Hoop, C. L., et al. (2014) Polyglutamine amyloid core boundaries and flanking domain dynamics in huntingtin fragment fibrils determined by solid-state NMR, Biochemistry, 53(42): 6653-6666. Full-text

- Kar, K., et al. (2014) D-polyglutamine amyloid recruits L-polyglutamine monomers and kills cells, J Mol Biol 426, 816-829. Here

- Kar, K., et al. (2013) β-hairpin-mediated nucleation of polyglutamine amyloid formation, J Mol Biol 425, 1183–1197. Full text

- Mishra, R., et al. (2012) Serine Phosphorylation Suppresses Huntingtin Amyloid Accumulation by Altering Protein Aggregation Properties, J Mol Biol 424, 1-14. Here

- Sivanandam, V. N., et al. (2011) The aggregation-enhancing huntingtin N-terminus is helical in amyloid fibrils, J Am Chem Soc 133, 4558-4566.

- Hoop et al. (2016) Huntingtin exon 1 fibrils feature an interdigitated β-hairpin-based polyglutamine core. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113(6): 1546-1551

- Lin et al. (2017) Fibril polymorphism affects immobilized non-amyloid flanking domains of huntingtin exon1 rather than its polyglutamine core. Nature Commun.

- Bagherpoor Helabad et al. (2024) Integrative determination of atomic structure of mutant huntingtin exon 1 fibrils implicated in Huntington disease. Nature Commun. 15, 10793

Related internet resources

- More information:

- PubMed Health Page on Huntington’s Disease

- Stanford’s very helpful HD Information site: HOPES

- Nederland:

- USA/international:

- CHDI Foundation – chdifoundation.org

- Hereditary Disease Foundation – www.hdfoundation.org

- Huntington’s Disease Foundation of America – www.hdsa.org

- Pittsburgh Institute for Neurodegenerative Diseases (PIND)

- Pittsburgh’s Center for Protein Conformational Diseases